A product team I once coached disliked the “no changes during the sprint” rule. It was hard to disagree as there seems to be an agile principle (#2 welcome late changing requirements; even late in the process) at odds with the value of focus and the Scrum rule of “no changes in a Sprint”.

They viewed it as a barrier, a straitjacket that prevented them from responding to new requests (yeah! That is a good problem to have, the team is embracing the agile mindset). Now part of me wants to ensure you all know that Scrum doesn’t say “no changes in the Sprint”.

It says there should be no changes that alter the original Spring Goal; only the Developers can decide to accept the change. Scope clarifications are ok as long as the Developers can absorb them (and most of them should if we teach how to plan capacity in a Sprint). Product Owners can alternatively terminate the Sprint and have it replanned, but only the Developers can accept changes made during the Sprint. So there is some coaching going on to help teams learn how to do this; this team was pretty mature.

Then, one quarter, they decided to remove it. Within two sprints, their boards resembled a game of “whack-a-mole": half-finished work, shifting priorities, and frustrated developers trying to hit moving targets. I had to sit back and let them "experience" this learning full-force, even though I saw it coming a mile away. It wasn’t until they reinstated the “Sprint Boundary” that they realized something important: the rule wasn’t slowing them down; it was protecting their focus and helping them finish.

What.

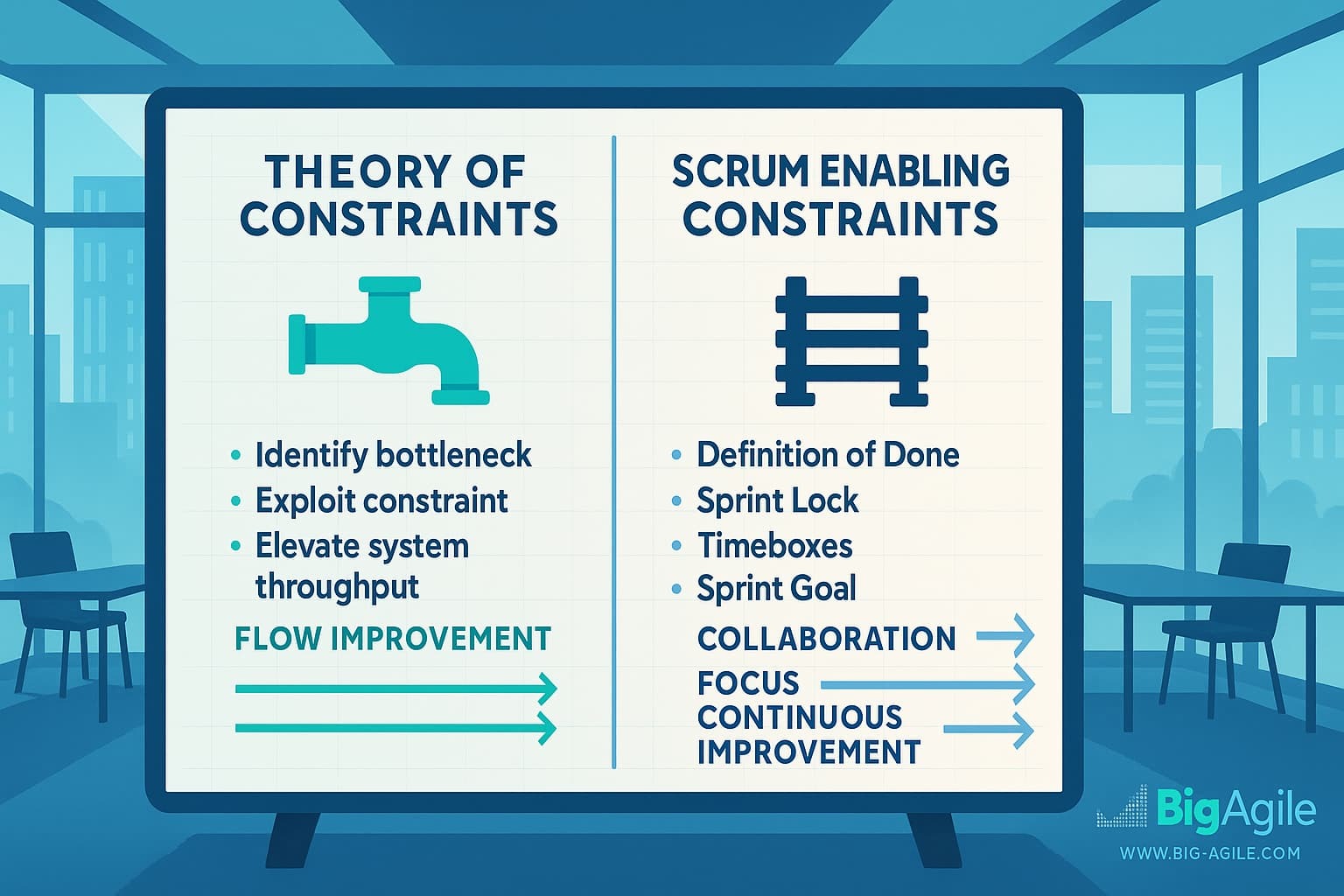

In the Theory of Constraints (TOC), the focus is on finding the system’s bottleneck, the limiting factor in throughput, and improving it so the whole system flows better. Scrum has constraints too, but they’re different. Instead of limiting throughput (still a good idea for a team), they’re enabling constraints (sometimes called generative constraints) that create conditions for collaboration, focus, and continuous improvement.

Examples include:

- Definition of Done (DoD): A shared quality standard that ensures every increment meets the exact expectations.

- Sprint Lock: The rule that no scope changes happen during the sprint, protecting commitment and focus.

- Timeboxes: Fixed durations for Sprints, Daily Scrums, Reviews, and Retrospectives to encourage regular delivery and reflection.

- Sprint Goal: A clear, shared objective that unites the team’s efforts.

So What.

The mistake many teams make is treating Scrum’s constraints as bureaucratic rules instead of creative boundaries. Remove them, and the discipline that enables agility erodes, work-in-progress balloons, quality slips, and focus scatters. Keep them, and they become the framework that lets teams experiment, self-organize, and learn without losing momentum. These constraints don’t restrict freedom; they channel it toward valuable outcomes.

Now What.

For teams struggling with Scrum’s constraints:

- Reframe them as tools: Understand what each is designed to protect or encourage.

- Inspect the results: When a constraint feels restrictive, try removing it for a sprint and compare outcomes.

- Reinforce purpose: Make sure everyone understands why the constraint exists and how it supports the Sprint Goal.

- Adapt with care: Modify constraints only when you’re confident the change won’t erode focus, quality, or predictability.

Let’s Do This!

The Theory of Constraints and Scrum both care about flow, but they work from different angles. TOC removes bottlenecks; Scrum adds enabling boundaries. When we embrace Scrum’s constraints for what they are, guardrails that promote discipline and creativity, we stop fighting the rules and start using them to deliver value more predictably.

Sometimes the fastest way forward is to respect the boundaries that keep you on track.