Let's be honest. Most teams struggle with how to get requirements into their new "agile" process. Take Scrum for instance. Scrum says you start with what is called a Product Backlog. Let's see what the Scrum Guide says about the Product Backlog:

The Product Backlog is an ordered list of everything that might be needed in the product and is the single source of requirements for any changes to be made to the product. The Product Owner is responsible for the Product Backlog, including its content, availability, and ordering.

The only guidance that the Scrum Guide gives for the Product Backlog is that it has these attributes:

Product Backlog items have the attributes of a description, order, estimate and value.

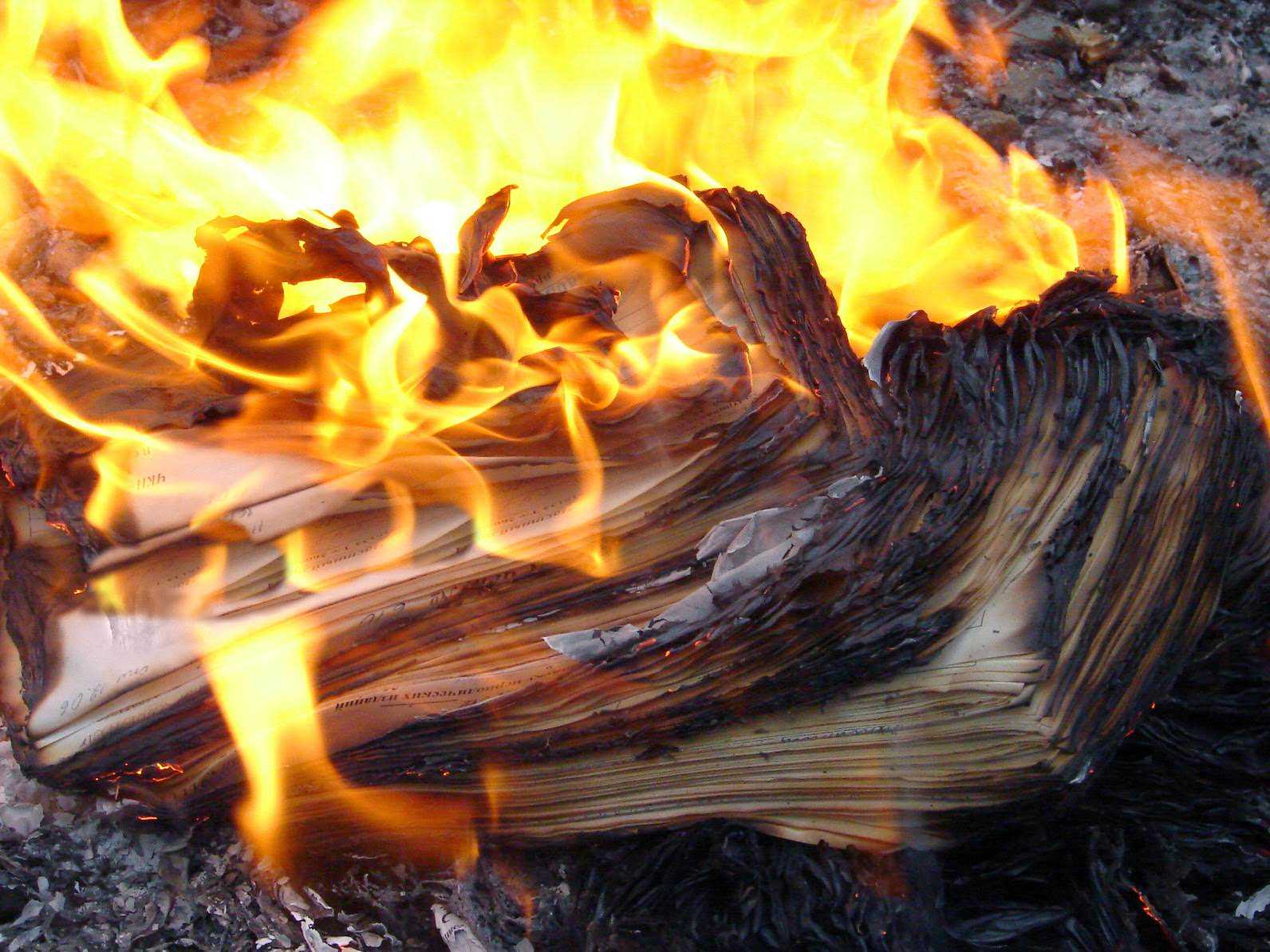

If you are coming out of a non-agile process, you are normally used to seeing requirements in the form of a BRD (Business Requirement Document), TRD (Technical Requirement Document), Functional Spec, etc...People spend countless hours writing these documents and in my experience, no one ever reads them completely. Typically because developers know the requirements have changed as soon as they get them or that the language from the customer is not clear, or worst yet, the customer really has no idea what they want. They know what problems they have, but rarely know exactly how to fix them with software (that's why they hired us right?)

Given that Scrum doesn't prescribe the actual technique to write requirements, we have to determine what works best for our team while adhering to the Scrum Values and Agile Manifesto Values / Principles. This is actually a powerful part of Scrum. That is why its called a process framework; not a methodology. Scrum doesn't prescribe how to do certain things. We are left to decide as a team. Professional teams usually have no problem figuring out the best way to work.

User Stories are a common way to get requirements into the Product Backlog. They are, however, largely mis-used. We actually borrow User Stories from the Scrum cousin process called Extreme Programming. Ron Jeffries formally provided some guidelines on a User Story after Alistair Cockburn visited the Chrysler C3 Team in Michigan (the first XP project).

Without going into detail about the history of a User Story (which is fascinating), let's talk about what the purpose of a User Story is for our Scrum Team. It is the vehicle in which we receive requirements. The difference between a User Story and Functional Spec is that the User Story is informal while the other types are formal requirements. The main reason we want the informal requirement is to foster conversation within the team about the requirement. We are moving from documentation to discussions (you can still document your discussions however).

Through the collaboration and discussion, the teams gain a clearer understanding of the need/problem and have a united view of the problem. Our customers / Product Owner brings the "What we need to build"; the problem. The Development Team formulates a solution (the "how we are going to build it"). We truly won't know if we have solved the customer's problem until they can empirically experience the product we built. A requirement document doesn't let the customer "experience" the product. Our goal in a Sprint is to turn those conversations into working product so that we can get feedback.

User Stories definitely have some typical formats to follow. The format however is more of a guideline not a rule. A widely used format is:

"As <some role>, I need <some feature>, so that I can get <some value>".

The main take-aways we want in a User Story is that we are communicating the actor of the story (who is this person / system that will need this feature). We then listen to what the customer is describing in their need (what is the feature they need). Finally observe the motivation. Why is it that they need to do this action? This is possibly the most important part of a User Story. As the team learns the reason the actor needs to be able to do something, they might pivot altogether on the solution and change the feature as they converse about what they are really trying to accomplish. The conversation is the most important part of the User Story.

User Stories typically start out a bit ambiguous and vague. Through the discussion, we gain clarity and can start breaking the work down into smaller pieces. We want stories to be actionable within our Sprint Time-box (stories that are too big to fit need to be broken down). We can then attach designs, discussions, and anything else we need as part of building the feature onto the User Story. We need to ensure the story is ready to go for a Sprint. There are many techniques that teams follow to do this; but one of the best tests to ensure your story is ready for a Sprint is found in Bill Wake's INVEST model. This is a good lens to ensure our team has the information needed to actually begin working on the story. We have to be comfortable with details emerging in the Sprint itself, but we do need a good guideline so that the team feels confident they understand the goal of the story.

User Stories can work for any types of work you are trying to accomplish. They are not relegated only for software teams. Give it a try next time you are trying to convey someting you need to someone else working for you. Also remember, that we don't expect every single Product Backlog Item in Scrum to be in the format of a story. It is a good practice, but there will be times it doesn't make sense. Take a defect for example:

"As a customer, I want this defect fixed, so that I am not frustrated".

Many teams spend hours trying to make sure the format is correct. If it doesn't make sense, then just log the item in the Product Backlog ("Fix Defect 1019283"). Usually those will come from the customer or a support team and have details on how to reproduce or a description of the error.

User Stories are a refreshing way to receive requirements in our Product Backlog. They do take some practice, so be patient and try them out. You will find that requirements through the exchange of conversation are much more valuable (and faster) than writing and NOT reading a requirement document.